The park bordered by 38th and 39th Avenues and Osage and Navajo streets isn’t North Denver’s largest, but it’s the subject of one of the largest discussions in North Denver right now. The park, officially called Columbus Park by the city, has also unofficially been known by some as La Raza park, and could be officially if an effort by Councilwoman Amanda Sandoval is successful in a new effort to change the name.

The fight over the Sunnyside park name isn’t new, but it’s been given new life in the wake of the civil unrest across the city and nation as protests have targeted monuments associated with historical figures who are now viewed negatively. One of those is Christopher Columbus. Protestors pulled down a statue of Columbus from Civic Center Park downtown, along with a Civil War monument. Others have been graffitied. The city has since removed another statue of Kit Carson, the Columbus Park sign, and has looked at removing others proactively before protestors do. The potential name change has also touched on still raw nerves for both the Latino and Italian communities, who have historically had conflict in North Denver, though that conflict hasn’t been as prevalent in recent years.

At the same time, the city has also formed a committee to analyze what other parks and buildings may have names that are now considered offensive, though the Columbus Park proposal is separate from the overall city effort.

Early History of Columbus Park

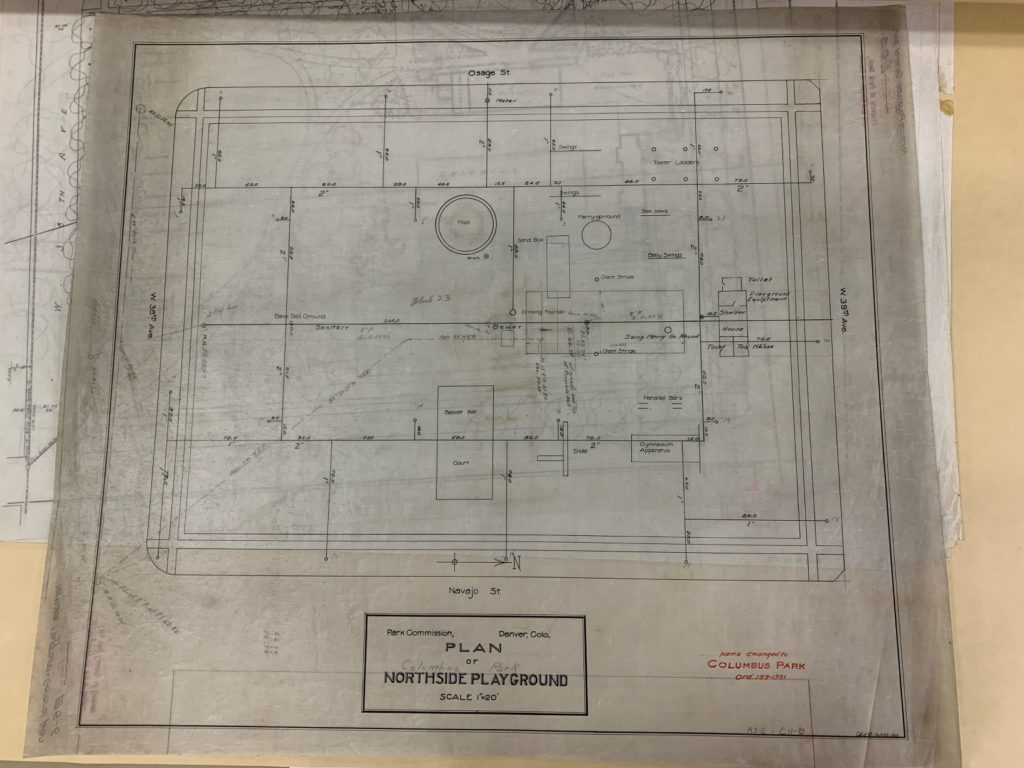

Documents show that the city acquired the land in 1906 and it was originally named North Side Playground Park. A deed provided by the Denver Clerk and Recorder’s office shows the city purchased the land from an out of state owner for $7,500. That amount is roughly the equivalent of $128,000 today. While original records are spotty, multiple people interviewed for this story said the Italian American community raised funds for the park and a 1998 Denver Post article refers to a $7,500 donation from the Italian American community in 1931, the same amount the city apparently purchased the land for. Councilwoman Sandoval also references a $7,500 donation in a letter to the city to begin the renaming process but was unsure of any historical documentation. In October of 1931, former Councilmember Eugene Veraldi proposed changing the name to Columbus Park; the renaming passed council unanimously. Whether the $7,500 donation actually occurred and if the amount is a coincidence or tied in some way to the sale or naming is still a point of contention today.

Interviewing residents of North Denver from the mid-20th century presents distinct stories that at some points align and at other points differ. Older Italians talk about conflict with newly arriving Latino residents at the pool that once took up much of the park, saying the new arrivals tried to displace them and their culture. Latinos talk about how the Italians were hostile and the new residents were barred from public spaces. The stories shared by interviewees shared the same locations and times, but other details were vastly different.

Suzanne Goeddel Anderson, now 80, grew up in the neighborhood in the 1940s and 50s and said the neighborhood was predominantly Italian at the time and the park was a place of pride for the community. She’s always known the park as Columbus Park. Growing up, she didn’t think much of the name but now understands why it’s problematic and isn’t opposed to a name change but wants to see something separate from either group. “I don’t really think it should be La Raza Park, she said. “I think it should be something more all inclusive.”

By the 1960s, the neighborhood’s population had shifted to be majority Latino. Local historian Phil Goodstein describes the transition and resulting culture conflicts in his book “North Side Story.” “Many Latino community leaders complained that the authorities discriminated against hispanos, especially targeting youngsters. The police were often exceedingly brutal in dealing with what those in power often dismissed as ‘Mexicans.’”

George Palaze, a retired Denver police officer who was often in the park during that era, paints a different story, recounting one time when he went to the park to arrest someone with an outstanding warrant and others in the park threw broken bottles and rocks at him and his partner. Palaze and his wife Barbara are organizing to keep the name Columbus Park which they see as honoring the Italian heritage of early North Denver residents. “My grandparents and great grandparents worked hard. They built North Denver. At times my family lived in chicken coops,” said Barbara Palaze.

In 1967, Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales founded The Crusade for Justice, a Chicano organization focused on civil rights issues: opposing police brutality, fighting job descrimination, and other civil rights issues. His daughter Nita Gonzales, who supports Councilwoman Sandoval’s effort to change the name to La Raza park, explained how the Latino community took over management and staff of the park. “When parks and rec would hire, they wouldn’t hire from within the community,” said Gonzales. “It wasn’t a transition. It was a revolution. We wouldn’t let the pools be open. We would block it. We would lock them down.”

In his book “The Crusade for Justice,” former organization member Ernesto Vigil describes the “splash-ins,” where Latinos would badger the white staff until they quit, who were eventually replaced by Latino staff. He says that by 1971 the park and surrounding area was run by people in the Chicano movement.

In 1981, one of the more pivotal moments in the park’s recent history occurred. Latinos from across North Denver had gathered for what had become the annual fiesta, according to Nita Gonzales, who was there with her then 11 year old son. She said the fiestas opened the pool each summer. That year, Denver police went into the park in riot gear, saying the participants didn’t have a permit. “We didn’t ask for a permit,” said Gonzlales. “The manager was hosting it. It was a community event,” explaining why they didn’t have a permit.

The police marched in from their rally point at Horace Mann school several blocks north of the park. Gonzales described the chaos: “They threw tear gas. They chased people down alleys. They let loose dogs on children running.” Gonzales explained her son was pulled into a neighbor’s yard to escape the dogs. “It was a police riot,” said Gonzales.

Efforts to Change the Park Name

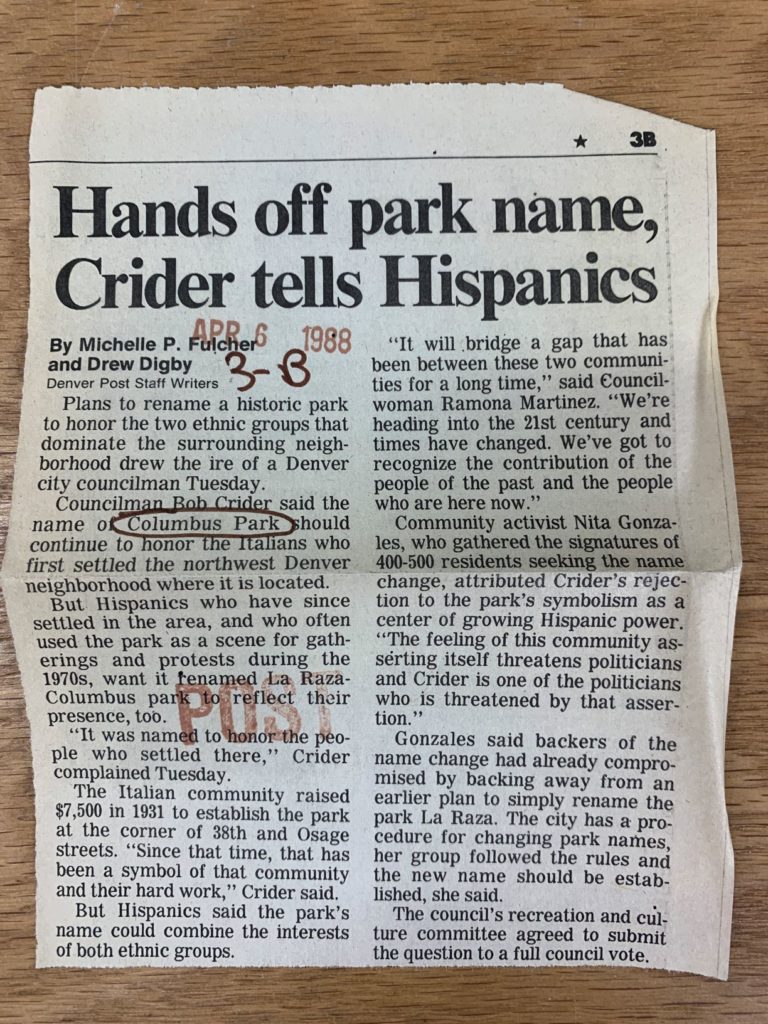

Throughout the 1970s, signs proclaiming “La Raza Park” would appear, but never with official approval from the city. In 1988, Councilwoman Debbie Ortega, then serving as a district councilwoman, pushed the issue to a Denver City Council vote, but council voted 7-6 to reject the change after strong opposition from the Italian American community in North Denver. Ortega, now an at-large council member, said that while she is not leading the current effort she is supportive and believes it has a better chance at passing. “There may be some (opposition),” said Ortega. “I don’t think it will be the same magnitude. People are recognizing the political climate we’re in.”

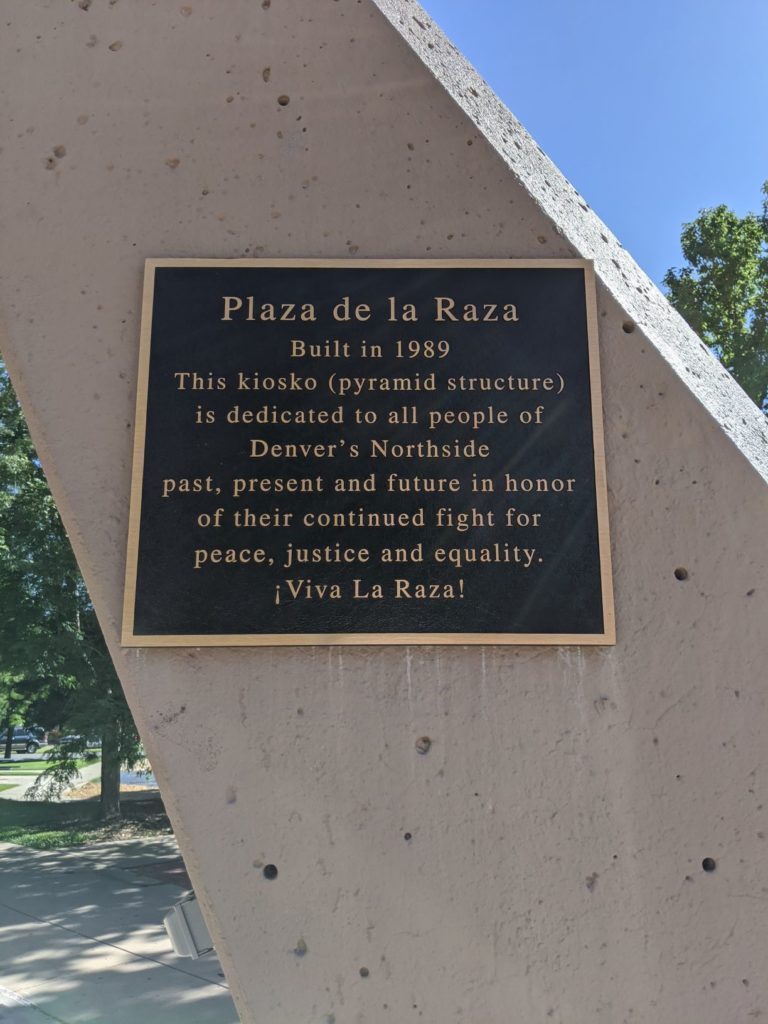

In 1989, during the tenure of Mayor Federico Peña, Denver’s first and only Latino mayor, a “Kiosko,” or pyramid structure, was erected in the park after the demolition of the pool, declaring it “La Raza Plaza,” but the park itself was still named Columbus Park.

Former councilman Rafael Espinoza attempted to create a dual name for the park as was done with (now) La Alma-Lincoln Park and Mestizo-Curtis Park, but also abandoned his effort.

For Councilwoman Amanda Sandoval, who just finished her first year in office, renaming the park is fulfilling a campaign promise. “I think it’s always been La Raza park so I’m just naming it what the neighborhood has called it,” said Sandoval. “It’s time to honor some of the history of America and not a man like Columbus,” noting that Columbus didn’t land on what’s now the U.S. and certainly never came to Colorado, let alone North Denver.

Meaning of “La Raza”

Part of the controversy surrounding the name change is related to the meaning of the term La Raza. Supporters say it’s an inclusive term meaning “the people,” while opponents say it’s exclusionary and point at another direct translation meaning “the race.” “I grew up with my dad saying ‘power to the people,’” said Sandoval. “I had always been taught that came from ‘¡Que Viva La Raza!’ I was always taught it meant ‘the people.’” Sandoval’s father Paul Sandoval served on the Denver School Board and in the State Senate and was a contemporary of Corky Gonzales.

Rudy Gonzales, Corky’s son, runs the Servicios de la Raza organization. Their logo translates the phrase to “Services for the People.” “‘La Raza’ has many connotations, just like many words in English, said Gonzales. “A word can mean multiple things to multiple people. To me, it’s always meant ‘the people. In other instances it can mean ‘the race’ — it’s up to the individual whether they want to be inclusive or exclusive with the term. For me it means the people. It’s an inclusive term.” Nita Gonzales also pointed out that Spanish has multiple dialects, but believes most residents of Denver would translate it to mean “the people.”

Judi Diaz Bonaquisti, a North Denver resident who identifies as Latinx and married into an Italian family, said she respects the role the name and park had for early Italian residents: many used Columbus as an icon to gain acceptance at a time Italians were heavily discriminated against. Despite that, today she supports the name change to La Raza. “It needs to be a bold name to embrace community and humanity, said Diaz Bonaquisti. “People are going to find controversy if they want to find controversy.”

Fellow North Denver resident Lynn Hendricks is among those who feel the name isn’t appropriate. “We moved here in the ’80s, Hendricks said. “We had never faced such nastiness in our lives. People yelling at us to go back to where we came from. Needless to say the Latino and Hispanic residents were not welcoming. Back then La Raza was weaponized to mean ‘us’ versus ‘them’ and we were told in no uncertain terms that we were not part of La Raza.” Hendricks said she believes the name Columbus Park should be changed but wants a third option as “La Raza is divisive.” She said she’s reached out to Sandoval’s office to express her view.

Susan Crawford, who moved to North Denver in 1992, agrees the term is divisive. “If you remove Columbus and change to La Raza, you are ignoring the Italian, Scottish, and Native Americans who were here before. Perhaps Northside or Sunnyside, or something that is simply a geographic feature. That would be more in keeping with the idea of the people’s park.”

Other Possible Names:

As people contacted Councilwoman Sandoval’s office, wrote into The Denver North Star, commented on NextDoor and other social media, and discussed the name change with neighbors, some pushed for a new name not tied to either Columbus or La Raza.

Paul Carabetta grew up in North Denver and his grandfather was a founding member of the Potenza Lodge, an Italian community center that began in the late 1800s and is still on 38th Ave today. He said many non-Latinos see the term as excluding all non-Latinos and the change is meant to honor Latinos only. He would like to see a large community process around the potential renaming, noting the conversation happening in East Denver. “Stapleton is doing a much better job of working within the community,” said Carabetta, frustrated with the binary option for the North Denver park. “No one has been given the opportunity to suggest names.”

Historian Phil Goodstein said the name change ignores a large portion of North Denver’s history, saying city leaders “need to emphasize the strong Italian influence on the neighborhood. It’s important to understand the strong prejudice against Italians in the neighborhood,” explaining that Italians weren’t considered white and weren’t welcome in many other parts of the city when they moved to North Denver.

Several residents commented on a thread on NextDoor with suggestions including Sunnyside Park, Northside Park, Pleasant Park, and others.

Councilwoman Sandoval said she is pushing forward with the change to La Raza Park. “The history has spoken,” said Sandoval. “For 50 years that park has been called La Raza park. I’m not into a process to find another name.” Sandoval said she is, however, open to a community process to name some of the still unnamed parks in North Denver, such as the park at 51st Ave and Zuni.

The Final Say:

Ultimately the decision will again come down to city council. Sandoval is going through the standard renaming process Parks and Recreation has created, which involves collecting signatures of support and then taking it to a council vote. She said she isn’t using the new city committee looking at parks and buildings because she started the effort before that committee was formed. Sandoval also said that the Mayor’s office reached out understanding that the name change was a campaign promise Sandoval made. “Anything with a commission group of people has to be vetted,” said Sandoval. “(Hancock’s office) said they would respect my process.”

A potential barrier to the name change is the persistent, but so far unsubstantiated, story that part of the land was donated by Italian American residents with the promise the park would be named Columbus Park, or that the money donated by the Italian American community was done with the promise that the park would remain named “Columbus Park.”

George Vendegnia formed a new chapter of the organization Sons of Italy in 1995 and has been one of the biggest advocates for Columbus Day parades and keeping the name Columbus Park. He, along with several other older Italian Americans interviewed for this story, all talked about documents they believe the city has that show the donation and say the city dropped previous attempts to rename the park when documents were produced. A spokesperson for Denver Parks said they have no records of a donation but that it is possible one was received. The 1988 Denver Post article referenced earlier in this piece refers to a donation at the time but doesn’t have additional details. The Denver Clerk’s office produced a bill of sale showing land that was purchased by the city but was also unsure of any donations. Brian Trembath with the Special History Collections at the Denver Library, shared approximately a dozen documents related to the park and explained their team was still in the process of doing extensive research due to the interest in the renaming. We will update this story if any relevant documentation is found and will make all documents available online.

Editor’s Notes: Much of this piece includes discussion of names, identities, and other descriptors. Understanding that terms can have powerful denotations and connotations, we make every effort to use appropriate terminology and will defer to a person or organization’s preference for the terminology they use.

- For purposes of referencing the park, we used “Columbus Park” in several instances because that is the official name according to the city, not out of any opinion or preference. Most instances in this piece simply refer to “the park.” Several interviewees referred to the park only as “La Raza Park” and that is represented in their quotes.

- In accordance with AP style, The Denver North Star routinely uses the term “Latino,” but uses other terms including “Hispanic,” “Latinx,” or “Chicano” where an interviewee uses those terms, which is why multiple terms are used in the piece. The term “Latinx” is a newer, non gendered term that is gaining popularity in some activist and progressive circles. Deference is given to any term a person or organization uses for themselves.

Some of the documents used as background information or directly referenced in this article can be found below. We’d like to thank the Denver Library, Denver Clerk’s office, and other offices who were helpful in researching this article.

The Spanish expression “la Raza” is literally “the race” and is not “the people” or “the community.” It is ethnic or racial and is not an inclusive term. The term was in wide use in Latin America in the early-to-mid-20th century, but has gradually been replaced by Hispanidad or Hispanic in many countries. It remains in active use specifically in the context of Mexican American identity politics in the United States.

Ms. Sandoval, for whom I voted, should say what she means when she wants to change the name to “La Raza Park.” It is totally a political move. Or she can use some of the more inclusive names suggested in your article such as “Northside” or “Sunnyside.”

Ron Bruner

I grew up in north Denver and the park was always Columbus Park, I believe that if we are going to rename the park it should ba a name that includes everyone. Several names have been suggested. Ms. Sandoval’s rufual to consider any other name makes this a simple political move.l