housing prices continue to increase

Image courtesy of Co-Own Company

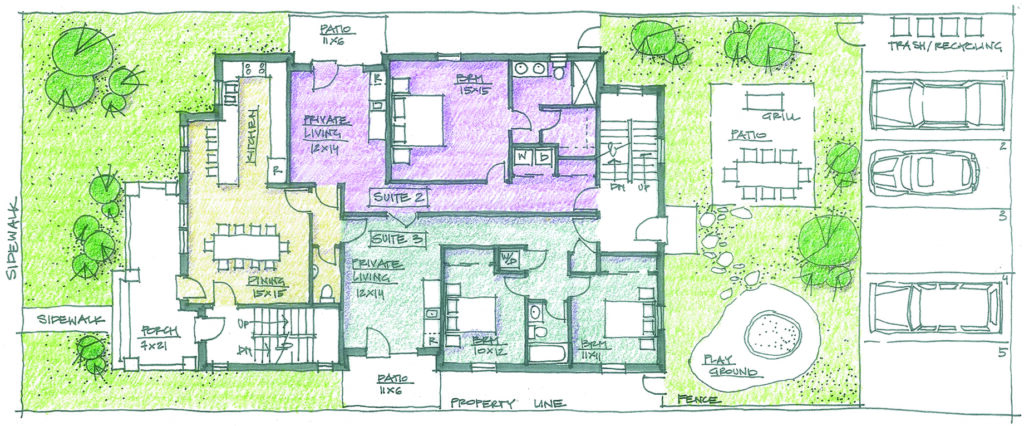

Jason Lewiston believes he’s building for the future while meeting a critical need in the present. “The fundamental issue is middle class people can no longer afford to buy homes in urban areas,” Lewiston explained. His solution? A newer idea known as co-ownership. The homes his business (Co-Own Company) are building have separate bedrooms, bathrooms, and a small kitchenette/coffee bar that’s designated for each person or couple, but then a larger shared kitchen and other rooms. Unlike most housemate arrangements, they aren’t rentals. Several people not only live together, but collectively own the home together as well.

According to data released by the Denver Metro Association of Realtors in November, the average sale price of a home in Denver was $691,081, a 17.7% increase from the year before, putting home ownership out of reach for many. To qualify for a mortgage of that size, a household likely has to make around $160,000 per year.

In contrast, Lewiston is selling a share of a 2,700 square foot townhouse in East Denver for $150,000. Next he’s looking at a home in Northwest Denver, possibly in the Sloan’s Lake area. Lewiston believes co-owned housing creates more economic opportunity for younger and lower-wage earners to stay in the city, build equity, and build credit. He expects some people to stay in co-owned housing for years, but others may want to move on if they want more space of their own, not unlike the traditional “starter home” model. When they do, they can sell their share and are likely better prepared to buy a full home solo than someone who spent those years renting.

Lewiston is also excited that his homes are “net-zero architecture,” meaning that environmental sustainability is built into each design. While there will be a garage and other parking space for personal vehicles residents already may own, he plans on having an electric vehicle shared for the house as well as solar and other green amenities. They are also targeting areas near light rail, bus lines, and other mass transit, believing that personal car ownership is diminishing and that trend is likely to continue. “Most people own a car and it sits 23 hours each day.”

If the concept seems too good to be true, it’s because there are a few hurdles to the idea. Not everyone wants a cohousing option of course, but setting that aside there are questions about how the houses fit into Denver’s restrictive housemate regulations, and not all neighborhoods have been welcoming to the idea of the slight density increase. While some registered neighborhood organizations (RNOs) in East Denver have tried to block similar projects, Lewiston remains hopeful as they expand to Northwest Denver. “We can’t pave more farms. Can’t put more cars on highways,” Lewiston said. “We need to reuse land wisely.”

Lewiston is outspoken about the support he sees for his project, even if that support isn’t always reflected in neighborhood groups and the city is still working on group living regulations that may impact uses for single family homes. “We’re not in the business of telling people who are going to be a family,” said Lewiston, who noted that many of Denver’s restrictive zoning laws are tied back to days of racial segregation and LGBTQ exclusion, which only benefited “Leave it to Beaver” communities. He sees support among every age demographic, but especially among those under 40 who are struggling to buy their first home in an increasingly expensive city.

Lewiston also noted that housing is the only area he knows of where people who have already purchased a product are able to control supply for others, and that the city would look ridiculous if restrictions were implemented elsewhere. “Can you imagine a sign in city council chambers saying people in this row have to be related to each other?”

A spokesperson for the city’s Community Planning and Development department said their staff is currently focused on helping Denverites through the pandemic in a variety of ways and enforcement of the current group living regulations are not a priority, especially where there are no visible impacts on the street or neighborhood. CPD has been working to update group living regulations, which have been a hotly debated topic across the city. “Part of the reason that we are looking at these policies is precisely because enforcement of the household rule doesn’t necessarily address the intent of the code, which is to ensure that residential uses don’t have an undue impact on neighborhoods,” adding that there are other code regulations for too many vehicles on a property, too many animals, or other problems.

CPD staff have been doing robust outreach as they look at updating regulations, including community forums and online input options and the new proposals are expected to be reviewed by city council in early February. Denverites interested in commenting on group living concepts can send feedback to planningservices@denvergov.org by Feb. 8 or visit www.denvergov.org/citycouncil for details on how to participate in public hearings.

While the group living conversations continue, Lewiston is moving forward with his plans. To see examples of the homes he’s building (single family homes he wants to make clear), visit https://co-ownco.com.

I am interested in purchasing a home in Denver with one other person (as opposed to three other people). If anyone reading this is interested in that as well, feel free to email me at megthornto@gmail.com. (Meg Thornton)