By Rebeca A. Hunt

Denver is a multimodal, transit-oriented city, with routes for cars, buses, bikes and walkers. All share the same streets. This is a legacy of the streetcar days of the 1870s to 1950. This month, we will look at the history of Denver’s streetcar system.

As Denver grew, adding new neighborhoods, there was concern that people would not move out of the core city unless they had a way to get from their homes to their work. Initially there was one option, the horsedrawn trolley that ran on rails.

The first transit company, The Denver Horse Railroad Company, formed in 1867, but did not build any lines until 1871 when the railroad began to bring more residents to Denver. It ran from Auraria to the new neighborhood of Curtis Park, north of downtown. The horses soon lost out to electric trolleys. The first ran in downtown Denver, powered by an underground line.

Invented by Denver University professor Dr. Sidney H. Short, it had one big drawback. If anyone stepped in the wrong place, they got a serious shock. By 1890, the underground wires gave way to overhead wires that became the norm for cable cars everywhere.

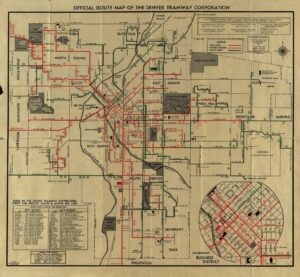

By 1873, the first north Denver electric line crossed the Platte River at West 16th Avenue, ran up to the top of the bluff, angled up to Fairview (West 32nd Avenue,) and over time headed west through the new town of Highland and out to another independent town called Berkeley. Soon there were spurs reaching out to each new development on the Northside. For a time, multiple companies competed to take streetcars to every quadrant of the city and its suburbs.

The neighborhoods that got the transit were generally middle- and upper-class where the residents could afford to pay the 5-cent each way fare. Working-class and immigrant sections did not generally get local transportation until later, sometimes not until the 1890s. The streetcars were useful and popular but had drawbacks. They were not flexible, being tied to their rails. And they were expensive to build and maintain. Also, their drivers were experts at their jobs who had a tendency to form unions and argue for better wages and working conditions.

The Denver Tramway Company, owned by William Grey Evans, was opposed to unions because he was opposed to workers trying to tell him how to run his company. In 1920 the transit workers went on strike, which led to multiple confrontations between strikers and strikebreakers. Eventually, after seven deaths and much violence, Gov. Oliver Shoup called in the Colorado National Guard to end the strike. By 1915, there was another problem facing the transit company.

Automobiles, once a luxury, now only cost $290 for a black, Ford car. Even the middle class could afford a Ford. Just before World War I, ridership had fallen by 9%. And as it continued to drop, the company began to lay off employees and cut back on routes. The streetcar system struggled on until the company and the city agreed to stop service and convert to more flexible and cheaper buses. That is how we got the bus transit system we have today.

Car commuters still outnumber bus riders. Especially in neighborhoods like ours, buses are still a great option for our residents. Have you ever wondered why we have small business blocks at the corners of many main Northside streets?

The trolley lines changed how developers planned out the neighborhoods. At some point every line came to a stop, turned a corner or crossed another line. These intersections were where riders exited and began their walk home.

This provided a perfect place to build a large building with grocery stores, butcher shops, saloons and other types of businesses. A few examples are the corner of West 32nd Avenue and Zuni Street, and where West 38th Avenue crosses Tennyson.

In the Tennyson example this encouraged completion of a small business district. As people walked by the businesses, they could just stop in for whatever they needed. So, in 2023, the streetcars are gone, but the rails are still there, just 3 feet under the current street surfaces.

Dr. Rebecca A. Hunt has been a Denver resident since 1985. She worked in museums and then taught Colorado, Denver and immigration history at the University of Colorado Denver until she retired in 2020.

Overhead wires were never the norm for cable cars everywhere. As in other major cities, Denver had two cable car lines powered by steam engines in power plants downtown that ran a moving cable between the tracks that the car would clamp on and off to for locomotion just like the current system in San Francisco. These then were replaced by streetcars with electric motors on the car with power coming from an overhead bare electric line which the cars connected with by a spring-loaded pole from the top of the car called a pantograph which slid along the bare line as the car moved (similar to our current light rail trains).