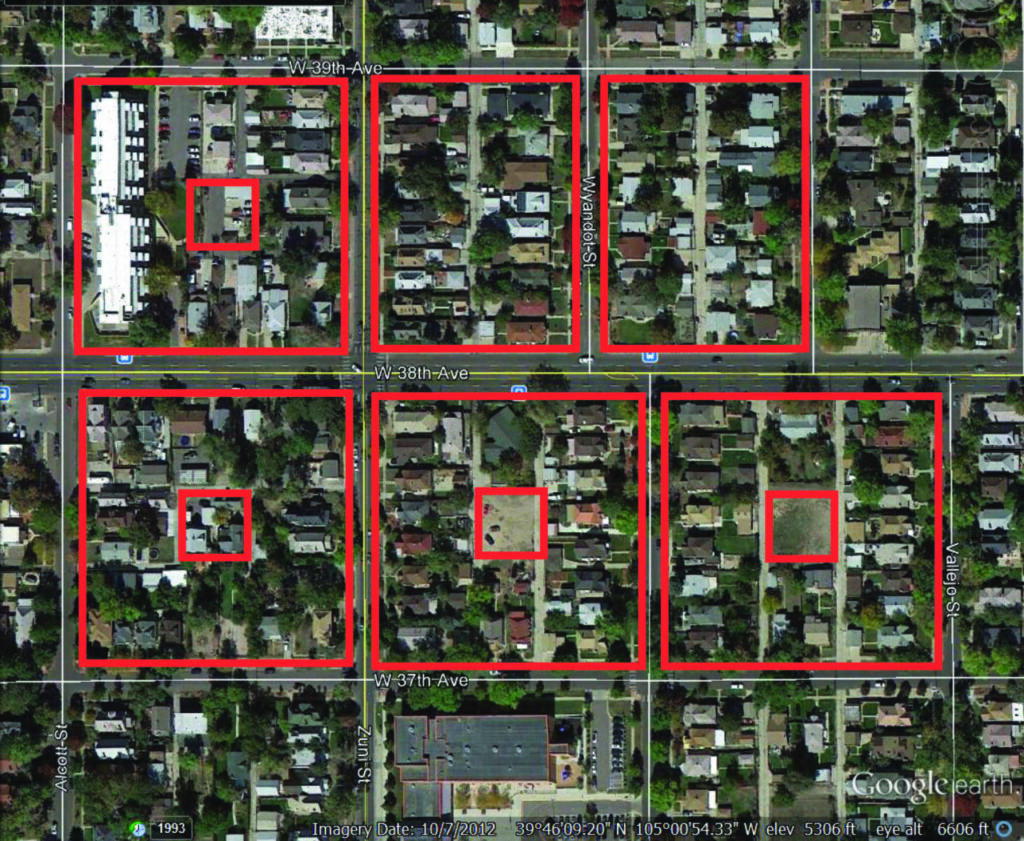

In the early days of planning North Denver streets, large square residential blocks— versus the rectangular ones of today—contained open interior lots. Considered public right-of-way space, these carriage turnaround lots provided a place for horse-drawn carriages to circle for a change in direction or for the horses who powered them to rest and graze.

Potter-Highlands Historic District is one of the areas in North Denver to find these historic features. You’ll encounter them walking through narrow H- and L-shaped alleyways in the blocks bordered by Federal Boulevard, West 38th Avenue, Zuni Street and West 32nd Avenue.

In the decades since horse-drawn carriages were common, a majority of carriage lots have gone on to become other things: paved parking lots, rows of garages, and even an occasional full-size house, right there in the middle of a residential block. Vestiges remain: stone walls, a coach house, even an occasional hitching ring, as if the horse will be right back.

In the late 1800s, these tiny public lots were important primarily to the handful of residents who could afford horse-drawn carriages, or to the small businesses that provided rides for a fee. Most people walked or biked their route, or walked the distance to a major road for public transportation like horse cars and, later, cable cars.

Today, a handful of carriage lots remain open in their original configuration. Ownership for the ones that remain falls to the city under its mandate to maintain right-of-way (ROW) for transportation and utility purposes. The city’s ROW properties include roads, sidewalks, alleys, and carriage lots, sites where public services take place (think police, fire, waste pick-up, storm water).

Denver Urbanism, a blog that “advocates a progressive pro-urban agenda for the Mile High City” covered these lots, and their dwindling numbers, in a 2014 post by contributor Chad Reisch. “Since these lots are publicly owned, they could easily be developed into community gardens, dog parks, pocket playgrounds, and communal places of refuge.”

The city will give up its responsibility for a ROW property if needs for transportation and utilities are no longer present or can be met in other ways. The Department of Transportation and Infrastructure (DOTI) manages the review process geared toward making that determination. Called “vacation,” the process begins with an adjacent property owner, or group of property owners, submitting a request.

A vacation request takes the form of an application, a checklist detailing the requirements of a site plan and legal description of the property, the completed site plan and legal description, and an initial processing fee of $1,000 plus a $300 legal description review fee.

recently platted standard rectangular blocks. Image courtesy of the city of Denver.

DOTI’s operations coordinator then forwards the request to numerous entities that have a three-week window to weigh in on its impact relative to their operations. Over 20 entities are notified, from CenturyLink, the city forester, and the property’s city councilperson to Denver Water, the Fire Department, and RTD. The entities respond with comments and an “approved,” “denied,” or “approved w/conditions.” The latter two responses are considered “protests,” where the applicant has the opportunity to work with the entity to “resolve the protest.”

The public is informed through a required 20-day posting of a notification on the property itself.

If a request makes it through DOTI’s steps, it is then charged a $300 ordinance fee and forwarded to City Council for consideration as a “Vacation Ordinance.” City Council’s part can take up to six weeks and results in a final determination of accepted or denied. If accepted, as directed by Colorado Revised Statute section 43-2-300, the ROW is absorbed back into the abutting properties closest to it. If there are multiple properties abutting the ROW, the ROW is portioned out so that each receives the section immediately connected to it.

into abutting owners’ properties, and the fenced-in yards that are currently on

city property

DOTI is currently managing 43 vacation requests, most submitted in 2020, 2021 and 2022. But a few go further back; the oldest open file dates back to 2015. According to Nancy Kuhn, Communications Director for Denver Public Works, an applicant has the opportunity to address protests that arise in the review process and the application remains open until “the applicant relays to us he/she can’t clear the protest, then we’ll close the request. There is no set expiration date.”

Several open requests pertain to properties in North Denver. One, near West 23rd Avenue and Eliot Street, is now a large dirt lot behind four residential lots, where 8-10 cars can be found parked. According to an application submitted in January 2021 by RealArchitecture LTD, a ROW vacation will allow for the development of an 18-20-unit townhome project.

Another open request, from 2018, can be found near West 35th Avenue and Shoshone Street. This application hit a few snags in the review process and doesn’t appear to be headed for City Council anytime soon. One reviewer pointed out that the alley should absorb a slice of the ROW in order to come into compliance with the current 16-foot alley width requirement. Another pointed out a need for an additional five-foot slice elsewhere in the ROW for the sanitary main. These concerns appear from city files to have been cleared up through revised drawings, and then approved by the entities who raised them.

But then, there were the neighbors. A number of them spoke out against the proposal through City Councilperson Amanda P. Sandoval’s office when it had the opportunity to respond to the request.

“The whole block was against it,” said Aaron Graber, owner of Silver Cloud Properties LLC, “The negative feedback was overwhelming.”

Silver Cloud had joined with neighboring property owners to submit a ROW vacation request in April 2018. The application stated that owners intended to turn three small homes and a triplex (on three side-by-side lots), rentals at the time, into single family homes with garages and possibly an over-garage ADU.

According to Garber, other properties on the block have access to the backs of their properties from an alley. But for his and the adjacent property, the ROW stands between the back of the property and the alley, preventing them from building garages.

Chuck Leidner, a neighbor opposed to the vacation, invited The Denver North Star to see for itself what his issues are. A brief tour revealed the sore spot. There are fenced-in yards used by the Graber triplex that sit on a portion of the ROW. Cars parked just south of the fence compress the space available through the alley. The ROW vacation application files for the property show that the fence was built between 2012 and 2014, before Graber purchased the property in 2016.

Leidner explained, “For me to pull out of my garage, on a good day, I have to make a three-to-five-point turn to avoid hitting them or my garage. On a snowy day and with everyone parked there, it means more maneuvering. Before the fence was built, there were an additional 12 feet, allowing everybody easy ingress and egress. Attempts at resolution have been fruitless. We’ve been bounced around by various city departments and ghosted by all.”

The fence did indeed come up in the review process, through Sandoval’s comments in March 2021, “This applicant built into the ROW, this needs to be remediated, to be clear this vacation should be denied and the fence and structures need to come down which are currently in the ROW.”

But DOTI isn’t the city department that would address the fence. That falls to Community Planning and Development. According to Kuhn, “The (vacation) request has not yet been officially denied. We are not requesting action regarding the fence while the case is open and these comments are addressed.”

Or until—in this modern-day, turnaround disagreement—the application is withdrawn.

Be the first to comment